Amy Mayes Photography

Amy Mayes PhotographyBEQ Today

Dr. Eric Patridge: He’s Just Getting Started

By Lynn C. Reyes

Photography by Amy Mayes Photography

Sometimes the BEQ Pride editorial team invites subject matter experts to be contributors of articles on various subjects. This time we asked subject matter expert Lynn Reyes to conduct an interview of one of BEQ Pride’s favorite STEM professionals who is part of the LGBTQ community. Lynn is a business value artisan and an expert on eminence for the IBM Institute for Business Value (IBV)—she is no stranger to the world of data and technology and more recently she has been studying talent and how organizations identify the types of talent needed when industries are in flux or transition.

As an artisan, she has a knack for seeing patterns, understanding a bigger story and making difficult things easier to understand. Her task was to talk with Dr. Eric Patridge and help our audience understand who he is, what he’s up to and most importantly why. In addition to being curious about him personally, I was eager to see if my tacit knowledge of him being an exemplar of LGBTQ-excellence could be shared with our audience of readers. And if we could successfully deliver a narrative that shares what happens when a person can truly be who they are without judgment—what brilliance they choose to bring to the world when they can show up and be included as their full selves.

Dr. Eric Patridge graduated from college with a BA dual degree in chemistry/molecular and cellular biology from Skidmore College; he earned a Ph.D. in integrative biosciences (with a specialty in chemical biology) from Penn State University and a Postdoctoral Associate in pharmacology from Yale University School of Medicine. Dr. Patridge is the founder of Out in Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (oSTEM) and was one of the inaugural BEQ Pride 40 LGBTQ Leaders Under 40.

~Robin

When my friend Robin asked me if I was willing to interview Dr. Eric Patridge, she noted that we have much in common, including a shared interest in data, patterns and inclusion. According to Robin, he “represented a unique voice in the LGBT community” and she felt my curiosity would be piqued. “Besides,” she said, “I know you’re interested in understanding brilliance — eminence potential — especially among millennials. Eric is perfect.”

She also knew I had been exploring different facets of talent that would lend themselves to authentic (human) intelligence and courageous leadership. What do authentic intelligence and courageous leadership look like in an era characterized by all sorts of disruption and exponential opportunities all enabled by information and technology and increasing societal complexity? Robin felt Eric represented a particularly interesting case study of leadership and talent disruption in STEM that needed a finely tuned ear and a kindred spirit to be sure the BEQ Pride audience could be educated, entertained and inspired by the possibilities enabled by his particular brilliance.

Of course, I looked him up. Some words that came across my screen were “pharmacologist,” “life science researcher,” “knowledge engineer”, “data scientist”, “ontologist”. Suffice it to say, he was more than a little interesting and I indeed accepted the invitation.

Patridge’s natural curiosity about the world informs his choice in vocation and in his purpose. Today he engineers data-driven solutions and ontologies at ReactiveCore**, an advanced technology company with offices in New York and Montreal. Before joining ReactiveCore*, Patridge worked as a subject matter expert, knowledge engineer and ontologist in life sciences clinical research.

“I want to help make people smarter about their decisions and about the world,” Patridge said.

Over the course of two weeks, we had several conversations. What intrigued me was Patridge’s ability to cultivate and apply multiple disciplines so expertly and fluidly. Connecting multiple disciplines into interdisciplinary pathways is his “craft”, one he began honing at a very young age so he could pass on to or share his knowledge with others. Fast forward a few decades and, to him, the process of engineering an ontology is more than science—it is a sensibility, that helps him understand what he is learning more deeply in order to share it with others.

“I love community and societal advancement. I also love intellectualism,” he said. “All three, however, can only happen when intellectualism isn’t cold — when it’s inclusive and compassionate.”

**ReactiveCore, has a dramatic new solution for combining disparate data models, rules and data into a cohesive single ultra-scale Enterprise Ontology rSuperNode—addressing the need for critical enterprise data within one secure platform in a constantly changing and expanding data landscape. Visit https://reactivecore.com

Ontology

There are two ways to define the term ontology. First, ontology is the philosophical study of being and the concepts that directly relate to being—becoming, existence, reality—as well as the basic categories of being and their relations. Second, contemporary ontology is an information science. It is the formal and practical representation of a set of information concepts within a domain and the relationships between those concepts. An ontology is used to reason about the properties of a particular domain, and it may be used to define the domain.

Patridge became interested in creating ontologies shortly after he began his pursuit of becoming a full stack data scientist. His interest in data science is entrenched in chemistry and the technology gap he perceives in the chemical landscape. He saw patterns in chemical structures that were similar to the hierarchical structures of ontologies.

“Ontology is a nebulous term,” he said. “It’s sort of an umbrella term that doesn’t make a lot of sense until you get into it. The key is context, critical questioning and conversation, which is why you need domain experts to participate.”

“I keep hearing people say, bring your authentic self to work,” Patridge said. “For me, that has a lot to do with diversity. I do think that in some ways historically and traditionally, [as a society] we had more conservative and rigid structures within which we had to work.”

These rigid structures limited our thinking about the possibilities in all areas including work, social interactions, academia and beyond. Less rigidity means more openness, freedom to be authentic and it increases the likelihood of innovative thinking and behaviors.

“Maybe it skewed our data and thought processes, requiring us to function in certain ways,” Patridge continued. “As we develop the permission to explore those spaces, we’re learning more about all of us. When we learn more, we can collectively advance.”

I had a fleeting moment of frustration as I realized the opportunity cost of rigidity—lost productivity, stalled advances in technology and the loss of talent to society. I also realized how most of our institutions (schools, governments, private, etc.) continue to fail to embrace and, more importantly, include the power of diversity. There was also a brief flashback to Biology 101: biodiversity ensures survival, for Pete’s sake!

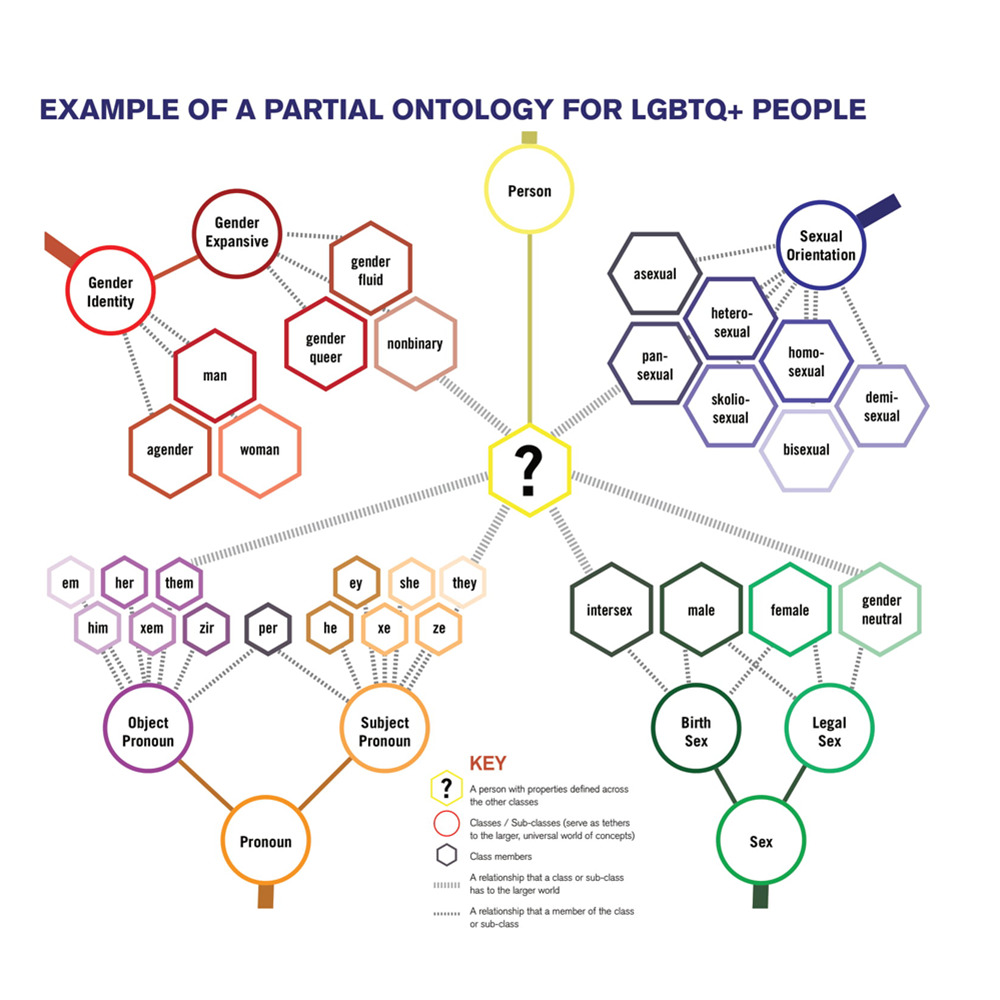

Pictured above is a partial ontology, an atomic representation of some defining biopsychosocial (biological, psychological and social) characteristics for LGBTQ+ people. The unnamed entity in the center of the graph is a person and a person has object properties defined across the other classes. Some possible names for these object properties might be “hasGenderExpansiveIdentity”, “hasObjectPronoun”, “hasSubjectPronoun”, “hasBirthSex”, “hasLegalSex”, “hasSexualOrientation.” For simplicity, all data properties for this ontology are hidden.

Becoming

Patridge lived in a relatively homogenous community in Connecticut and had a patrician upbringing steeped in learning, service and religion. His family valued education and encouraged him to pursue different interests. In addition to being academically inclined, he also played the clarinet, French horn, cymbals, and xylophone. He was a Boy Scout. He even served on the altar for seven years. His mother started family mass at their local parish, and his grandfather helped to cultivate and grow the Third Order of St. Francis in the state of New York.

Patridge’s youth, however, was not without its challenges. High school was particularly difficult. He experienced the peer pressure reminiscent of the extremes portrayed in high school teen movies and struggled to find a sense of place and community given his keen intellect and musicianship. He also wrestled between his religious upbringing, his faith and his emerging sexuality. He painfully realized in that small community at that time, “Science, religion and sexuality didn’t mix as well as I’d hoped they would,” he said.

It was a six-week summer theatre camp and the thriving artistic community within it that provided both salve and sanctuary. The community brought together different types of kids with different artistic interests. They were open to people who had different interests, not just the interests themselves—the magic was in the diversity.

There, Patridge found a safe community and friends who enabled him to grow in new ways while keeping his sense of self and spirituality intact. During our conversation about camp, he recalled a quote by Bernard Meltzer from memory, “A friend is someone who knows the song of your soul and sings it back to you when you’ve forgotten the words.” I suppose he was saying the camp experience was like having a place to remember who you are.

By his senior year in high school, and two years of summer theater camp, Patridge had written and produced a play titled “Lessons Worth Dying For”, a drama about high school, manipulative relationships and drug use. He enjoyed the experience of bringing a group of people together around a creative idea.

He briefly returned to playwriting in graduate school, this time an allegorical play about the Bible, specifically Genesis, in which he explores the creationism/religion versus evolution/science debate.

“It’s funny to me that scientists like to fight against creationism,” he said. “You have people who fight against evolution. And I’ve to come to this understanding that makes me feel like they’re one and the same.”

Patridge purposefully left the play unfinished because he wants to tackle it after he has more life experience and a better perspective.

I asked Patridge when he became interested in science, particularly chemistry because all signs seemed to point to him studying theater in college. The spark was an AP chemistry class in his senior year of high school. It was the first year the class was taught at his school and he had a particularly exceptional teacher. His teacher had a Ph.D. in Chemistry, invested in the inaugural class of six students with Saturday classes and extra time that was inspirational to them as well. But it was in college where most of his interest in the sciences came to fruition.

Skidmore College offered a uniquely interdisciplinary environment rooted in a core class — The Human Experience — which explored every possible facet of the human being. Going in, Patridge already had a great interest in learning more about the world, and this course took his interests to another level. The momentary blurring of boundaries across differences to see what would emerge and the exploration of seemingly disparate perspectives to gain new insights is a technique he relies on today. The science courses he took all used the human being as context. “We did a lot of orthogonal learning,” he said. He was well on his way.

Existence

There are two experiences that Patridge shared that explain so eloquently what it feels like to truly belong. Talking about his first Pride in NYC he paused several times, it was “hard to communicate how it feels to be yourself for a whole weekend and do nothing but celebrate that for the first time. Because when you’re at a Pride event, it ends up being the first time that you feel like you’re in an environment and a place that honors you and respects you, values you and wants you to have the best time that you can… and sees who you are and [you] know it.”

His first time at an Out&Equal Summit, he had a similar emotional experience, this time in a professional setting. IBM sent him to Out&Equal and to participate in a roundtable event at the Human Rights Campaign. He said IBM “took care” of them, black cars shuttling them to and fro in DC, hotels and meals and it “made me want to share this with other people,” he said. The experience made him value himself in a different way.

Patridge’s graduate studies in chemistry and molecular and cellular biology at Pennsylvania State University also required data savvy, technological literacy and engineering. His ability to cross disciplinary boundaries was heightened by his curiosity about some Resource Description Framework (RDF) graphs of chemical structures stored in databases structured much like ontological hierarchies. Because he was already quite familiar with relational databases and ETL (extraction transformation and loading of data) for clinical data, the idea of applying ontology to clinical data seemed to be a natural progression. Where others focused on specific “worlds”, and even as he focused on a few of his own, he saw a universe of worlds yet to be explored.

He soon jumped into another opportunity, this time building an ontology for food nutrition for a business case. He started the effort, “without really even knowing what I was doing. So, it was really sort of an ongoing relationship with the understanding of what ontology was,” he said. He and his team were able to build a robust ontology that could be used in many different ways.

From there he made the move to ReactiveCore where he uses ontologies in a very different way. There he uses both systems centric ontologies as well as domain canonical ontologies to understand, use and manipulate ontologies for business application, specifically in the world of big data and cloud computing.

From there he made the move to ReactiveCore where he uses ontologies in a very different way. There he uses both systems centric ontologies as well as domain canonical ontologies to understand, use and manipulate ontologies for business application, specifically in the world of big data and cloud computing.

As Patridge sought to close gaps in understanding, using and manipulating big data in the chemical landscape, his inner Trekkie explored the unfolding universe. Ontologies can work everywhere! And ontology as philosophy and as an applied science would help foster his own intellectual understanding within and across the worlds in that universe, hopefully spurring intellectual curiosity and understanding in others along the way.

As Patridge was getting more involved in LGBTQ community activities, he formed some opinions based on his observation of his community’s perspective on learning and intellectualism that were particularly bothersome to him. While he was envisioning progress and advancement for the community into new shared outcomes and better shared futures, he realized that those who had a stake in those outcomes and futures weren’t necessarily prepared for or interested in the journey. Paradoxically, many communities are often cold to a new way or different possibilities and shun the intellectual rigor and idealism that brings new facts to light.

Once when he was speaking to a group of 50 LGBT students about STEM, he watched one student yawn conspicuously, stretching out his arms expressively to show that he wanted to be somewhere else. Somewhere more fun. There was something in the culture — his community’s culture — that in his view shunned the hard work (and by extension the increased likelihood of success) of pursuing goals and dreams for the future, even though they had the capacity and ability to move the needle forward. It seemed that more times than not when faced with a choice, many people chose “to socialize, party or be otherwise fashionable” rather than reach for a better future.

“Some of what I want to do with my life is to help offer more avenues and safe spaces to increase the statistical likelihood of people being able to achieve [their] intellectual passion, compassion and success,” Patridge said. “We’re going to see a lot of things change in our world. I think, until we have more avenues to compassionate intellectual realism that work, we will continuously be drawn back[ward].”

Creating oSTEM

In 2005, Patridge and fellow students were sponsored by IBM to participate in a focus group exploring the advancement of LGBTQ+ students in STEM professions as part of the first Out for Work conference in Washington, DC. During the event, participants identified the need for an inclusive organization for technical students in the LGBTQ+ communities. This prompted Patridge to found oSTEM (Out in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics); there had not been one prior focused on serving students.

By 2010, Patridge was at the Yale School of Medicine and oSTEM achieved 501(c)(3) status as a national nonprofit association for LGBTQ+ students in the STEM fields. Patridge served as its President until 2017.

Patridge is a self-proclaimed mosaic, “a mosaic of different aspects of things… in some ways I’m unique particularly to my interest in merging disciplines and the blending of things because that’s hard to do,” he said.

As he said that, he reminded me of an article regarding new skills for STEM students. In short, the article suggests that engineers of the future will have to be different, educated in a different way—more communication skills, the ability to work in teams, global knowledge, and an entrepreneurial outlook as much as they will need technical depth. They need to be life-long learners and have more liberal arts exposure.

Realities

What had been raw talent, natural curiosity and creative expression through the arts and writing evolved over time. While Patridge had been academically focused on science, engineering and ontology, most of which would be obsolete or have evolved upon graduation, it was the softer skills that honed his STEM knowledge as a craft — a merger of apparently disparate disciplines to create a new lens.

Today he applies his mosaic to focus on developing solutions and creating new worlds in his professional life and personal interests. What’s common across both is his habit of exploring and examining a topic from multiple perspectives, then merging those perspectives through an interdisciplinary lens.

Patridge continues to seek ways to make chemistry relatable using ontologies to reveal new market opportunities. Recall earlier that he was drawn into the practice of ontology by looking at gaps in the chemical landscape.

I asked about some of his own imagine-if ideas. The response: “Caffeine”. “Markets”. Now I could relate to that!

Caffeine, Patridge said, is a molecule that everybody encounters on a daily basis. There are different products and varieties, and certainly a global market for it. But, how many people know the structure of caffeine? I didn’t, but I did say that sometimes I wished I had an IV drip of it when needed and I certainly was keen on the idea of new markets. What about new molecules?

The idea of discovering new molecules is exciting for any burgeoning scientist. There are different varieties with each potentially the basis for new markets. The challenge, however, was the lack of technology to organize what scientists already know—this is where ontologies and chemical structures create new worlds in Patridge’s mind.

Patridge saw how so much productization and market valuation was based on abstractions from chemistry like in coffee. Coffee is probably most valuable, he said, because people buy it for the caffeine. And the coffee market is approximately $48 billion annually. His question was, “What would change in our world if we brought more structure to this lens, especially when all of biology is chemical and chemical-based?”

Patridge perceives a revolution in chemistry at some point where we could potentially build a different stock market around the value of certain molecules, like caffeine, while mitigating the risk of humanity not knowing how to properly identify, interrogate and evaluate a molecule.

Patridge’s intelligence is authentic, not artificial. There’s a generosity to his intellectualism and his interdisciplinary craft is going to help address big challenges and create value personally, professionally at ReactiveCore and beyond. And he’s still just getting started.

Lynn C. Reyes is a Business Value Artisan and is on the advisory board of BEQ Pride. She spends her days as an IBMer.

Business Equality Pride (BEQPride) is the first publication from the BEQ family of national print and digital magazines exclusively addressing the needs of LGBTQ small-to-medium sized businesses, entrepreneurs and professionals.

0 comments